How Michigan Became the Epicenter of the Modernist Experiment

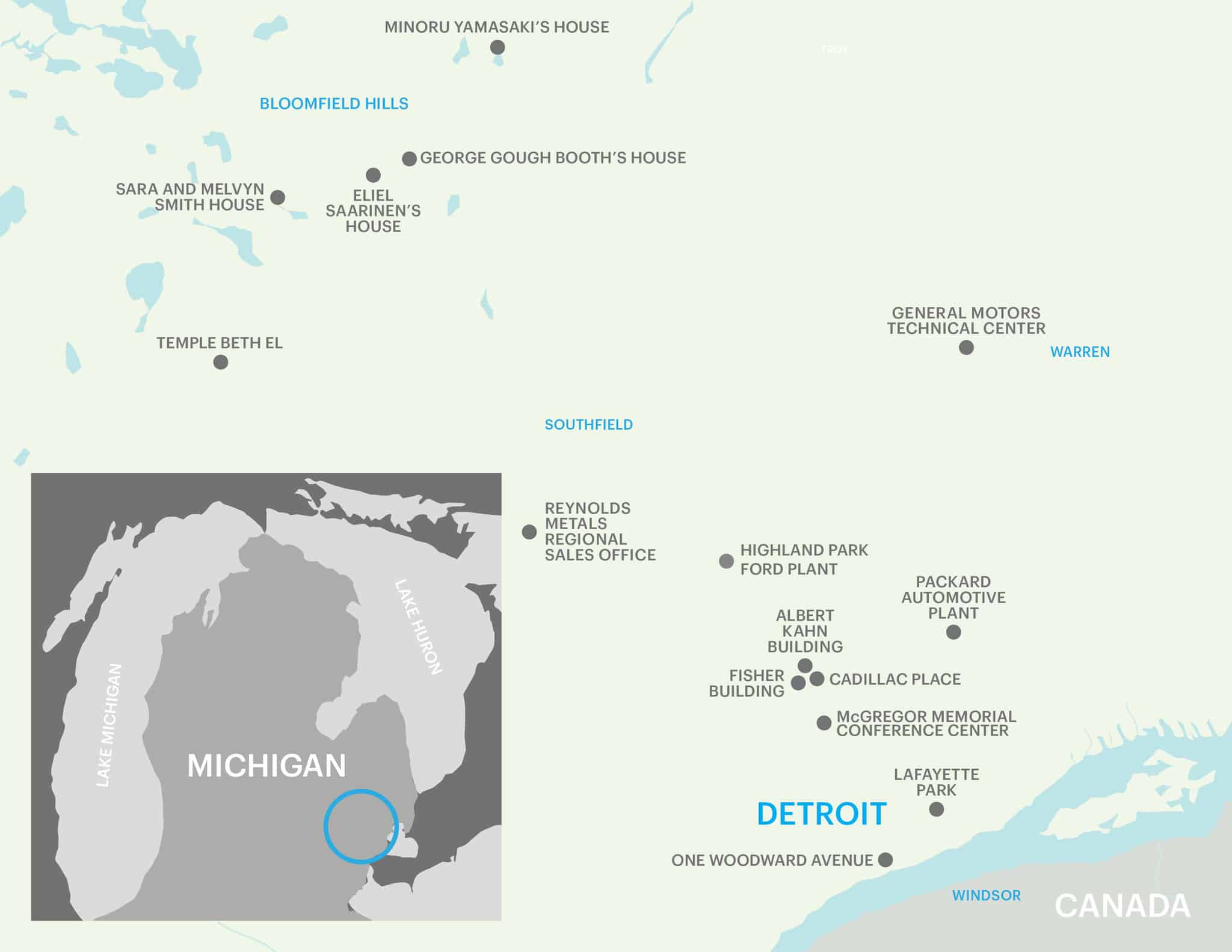

A perfect storm of manufacturing money, ample space and robust industry created one of Modernism’s most fertile and important outposts in and around Detroit.

I. The Plant

IN 1908, the year Henry Ford introduced the Model T, what he called his “car for the great multitude,” the architect Albert Kahn submitted designs for Ford’s factory in Highland Park, Mich., near downtown Detroit. In 1913, three years after the company moved into the building, this would become the first automobile facility in the world with a continuously moving assembly line, and over the next 14 years, the site of creation for millions of Model Ts. It was here that Ford implemented the eight-hour workday and the five-day week, with livable wages for unskilled workers, which did as much to modernize America and rejigger its class system as did the Model T itself.

Kahn came from humble means. He was a Jewish immigrant from the former Kingdom of Prussia whose family had settled in Detroit in 1881. He founded his eponymous firm in the city in 1895, at the age of 26. Early in his career, with the 1904 design for Building 10 of the city’s Packard automotive plant, Kahn revolutionized industrial architecture by replacing wood materials with reinforced concrete, a safer alternative that also allowed for more dramatic structures. The Packard plant was a small city unto itself that at its height employed 40,000 workers in a 3.5-million-square-foot complex with vast rows of windows. (Kahn, who designed the entire complex, was, according to a 1956 article in the Detroit Free Press, “an apostle of sunlight,” someone who “didn’t think much of windowless factories.”) Ford would hire Kahn on the basis of Building 10 and other similar factories he worked on, which pulled American design into the 20th century.

The same year Kahn submitted his designs for the Highland Park plant, he completed work on a manor home about 20 miles north of the city, in what would become the suburb of Bloomfield Hills but was at the time still farmland. The commission came from George Gough Booth, the publisher of The Detroit News. Booth and Ford could not have been more different. During the 1920s, Ford, who once said, “I don’t like to read books,” also owned a newspaper, The Dearborn Independent, which ran a year-and-a-half-long series of anti-Semitic articles that began with a piece titled “The International Jew: The World’s Problem”; a connoisseur of Asian art and literature, Booth was scholarly, and a proponent of the Arts and Crafts movement.

Booth had ambitions of creating an estate that would put the movement’s principles of simple, handmade design into practice. By 1932, his property had prep schools for girls and boys, an Episcopal church and, most significantly, the Cranbrook Academy of Art, an American Bauhaus in rural Michigan and a precursor to other experimental American art schools such as Black Mountain College. The academy’s first president, the Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen, designed most of the campus and attracted some of the great minds of 20th-century Modernism, including visitors like Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright, and students like Ray and Charles Eames. Lecturing at the school in 1945, Wright reportedly advised the young students to “Work, work, work — night and day!”

Wright’s mantra is as good as any at summing up the Modern era — constant toil in the name of progress. If Michigan isn’t the first place that comes to mind when considering this period — unlike, say, Germany or France in the 1920s — it should be. The presence of Ford in the city and Booth in the country was enough to make Michigan ground zero for the Modernist experiment, which was, on an aesthetic level, concerned with clarity and flexibility: Ford wanted all the messy components of manufacturing to be housed under one enormous roof, and Kahn made it so. But ideologically, architectural Modernism was more complicated, rooted in the idea that if one were to reshape an environment in a kind of magnificent, functional order, then that environment would encourage a level of social harmony and cohesion. This experiment failed, of course, but its remnants still stand throughout Michigan, making the state home to perhaps the most diverse and best-preserved collection of early Modernist experiments in the world.

II. The School

THERE IS NO greater testament to Michigan’s role in Modernist design than Cranbrook. Eliel Saarinen — who arrived in America in 1923 from Helsinki and taught for a year at the University of Michigan, where Booth’s son Henry was one of his students — was soon poached by Booth to design and run his art school. Saarinen’s campus home, which he designed in 1928, is one of the great structures of its time. Here was something altogether new, hidden in the Michigan countryside. Inside, every corner, every angle was considered in masterful detail to such an extent that Saarinen even had a paperback copy of Jack London’s “The Sea-Wolf” bound in leather so that it would blend better with the surroundings. The house became Saarinen’s studio, where, at least as much as Ford’s factories, a new direction for American design was conceptualized.

Saarinen was the primary recipient of Booth’s patronage, which likely rankled his chief rival and admirer: Frank Lloyd Wright. (“All I learned from Eliel Saarinen was how to make out an expense account,” Wright once said, though he visited Cranbrook often.) On a recent visit to the Saarinen House, Gregory Wittkopp, Cranbrook’s director of collections and research, suggested to me that Wright may have opened a fellowship program at Taliesin, his 800-acre home and studio in Wisconsin, at least in part as a way of competing with Saarinen and Cranbrook.

Near Cranbrook’s campus sits one of Wright’s most perfectly preserved houses, which was recently gifted to the institution: the Sara and Melvyn Smith House. Wright may have been based in Wisconsin, but Michigan, with its wealth from the auto industry and its expanding suburbs, was the ideal environment for his conception of the single-family house. The Smiths, Wittkopp tells me, were dream clients: public schoolteachers in Detroit who were obsessed with Wright’s designs. The house he designed for them cost $20,000 to build; to save money, Melvyn served as the general contractor and paid his workers on a 10-year installment plan. In 1950, the Smiths moved in. After Melvyn died in 1984 and their son moved to California, Sara essentially packed a bag and left, leaving the house wholly intact. Today, it is a remarkable portrait of not only the Smiths but postwar America: There is a foam Naugahyde club chair in the sunroom, a book called “The Sexually Responsive Woman” on a shelf, plastic plants and a diverse range of objects (a Paul Evans cabinet, numerous ceramic vessels) purchased direct from the studios of Cranbrook students, all orbiting around the hearth, the house’s center of gravity. Saarinen died the same year the house was completed. But it offers a palpable sense of the fleeting set of circumstances that once made this unprepossessing Michigan suburb a laboratory for the future of American living.

III. The Architect

BY THE MID-50S, the Detroit Free Press was claiming that “Detroit has become to many architects what Mecca was to Mohammed — a sacred city.” World War II had ramped up manufacturing as Kahn’s factories became entrenched in the wartime effort, with Detroit playing a key role in President Roosevelt’s “arsenal of democracy,” adding 400,000 people to its population between 1940 and 1944. After the war, many of these transplants stayed, leading to a construction boom, which was aided by the G.I. Bill for returning veterans and by funding from the so-called urban renewal policies that formed the backbone of President Truman’s domestic program. According to a 1961 feature in Progressive Architecture devoted to Detroit, there were dozens of major architectural offices in the city and in its fast-growing suburbs, including Birmingham, Southfield and Bloomfield Hills; some 50 offices opened between 1955 and 1961.

Numerous icons of Modernism were realized during these years, including Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Lafayette Park, a residential development (designed with the city planner Ludwig Hilberseimer and the landscape designer Alfred Caldwell) of glassy townhouses anchored by three huge glass-and-concrete apartment tower cubes. The complex was built on the site of Detroit’s Black Bottom, the heart of the city’s growing African-American population that was razed in the early 1950s, one of countless examples of minority communities routinely targeted by urban renewal projects receiving vast sums of government money for “slum clearance.” Lafayette Park was, as Danielle Aubert, Lana Cavar and Natasha Chandani argued in their 2012 book about the project, “Thanks for the View, Mr. Mies,” the epitome of “a Modernist utopian fantasy of democratic leveling through urban renewal,” where people of different classes and races would share a uniform housing model, beneath which the sins of the past could be buried.

Mies van der Rohe was one of many architects drawn to Detroit by opportunity, but the most prolific and high-profile builder of this period was Minoru Yamasaki. Born in Seattle to Japanese immigrants, Yamasaki earned an architecture degree from the University of Washington before moving to New York in 1934; eight years later, he brought his parents to live with him as they had been marked for imprisonment in one of the United States government’s internment camps for people of Japanese ancestry. In 1945, he would relocate the family to Detroit after receiving a job offer from Smith, Hinchman & Grylls, one of the city’s most prestigious firms. But his career was also bound to the nation’s prejudices. According to Dale Allen Gyure’s recent biography of the architect, the Yamasaki family’s “Japanese heritage made them unwelcome” in the city’s wealthiest enclaves, though Yamasaki could afford them. He eventually bought a piece of farmland in an unincorporated area outside the village of Troy, where he’d later build his own office.

Booth had ambitions of creating an estate that would put the movement’s principles of simple, handmade design into practice. By 1932, his property had prep schools for girls and boys, an Episcopal church and, most significantly, the Cranbrook Academy of Art, an American Bauhaus in rural Michigan and a precursor to other experimental American art schools such as Black Mountain College. The academy’s first president, the Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen, designed most of the campus and attracted some of the great minds of 20th-century Modernism, including visitors like Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright, and students like Ray and Charles Eames. Lecturing at the school in 1945, Wright reportedly advised the young students to “Work, work, work — night and day!”

Wright’s mantra is as good as any at summing up the Modern era — constant toil in the name of progress. If Michigan isn’t the first place that comes to mind when considering this period — unlike, say, Germany or France in the 1920s — it should be. The presence of Ford in the city and Booth in the country was enough to make Michigan ground zero for the Modernist experiment, which was, on an aesthetic level, concerned with clarity and flexibility: Ford wanted all the messy components of manufacturing to be housed under one enormous roof, and Kahn made it so. But ideologically, architectural Modernism was more complicated, rooted in the idea that if one were to reshape an environment in a kind of magnificent, functional order, then that environment would encourage a level of social harmony and cohesion. This experiment failed, of course, but its remnants still stand throughout Michigan, making the state home to perhaps the most diverse and best-preserved collection of early Modernist experiments in the world.

But, Gyure recounts, Yamasaki did find wider acceptance within the city’s community of architects, especially from Eero Saarinen, the son of Eliel, who started working for his father’s firm in 1936 and was soon receiving major commissions. Among these was the General Motors Technical Center in the Detroit suburb of Warren, which upon its opening in 1956 established the template for the modern corporate campus, an “Industrial Versailles,” as Architectural Forum put it that year, with a network of office buildings to accommodate some 4,000 staffers, arranged around a 22-acre reflecting pool. What Kahn did for industrial architecture, Yamasaki did for office buildings. The architect created many great buildings in and around Detroit, most of which were made for such modest purposes that they’ve spent decades hiding in plain sight. In the suburbs are a series of adventurous offices — the American Concrete Institute, the Reynolds Metals Regional Sales Office — that make use of his signature glass curtain walls and intricate grille work, which from a distance looks like textile patterning. Near Cranbrook is the 1974 Temple Beth El — its white concrete frame suggesting a huge tent revival.

Yamasaki also designed much of the grounds of Wayne State University, a public school near downtown that feels both very far from Cranbrook and yet also aesthetically connected to it. One morning last winter, Yamasaki’s Helen L. DeRoy Auditorium was filling up for class. A parade of students marched into this strange gray brick of a building, whose arched ornamentation recalls the angle of the thatched roof of a Buddhist temple. Surrounded by a shallow pool — unfilled these days and clogged with dirty leaves because it is too expensive to repair and maintain — with a walkway leading over it to the entrance, the auditorium was meant to appear as if floating, and it conjures both traditional Japanese architecture and some kind of crash-landed spaceship.

Yamasaki won the commission for New York’s World Trade Center in 1962 and appeared on the cover of Time magazine a few months later — an honor afforded to only about a dozen other architects, Eero Saarinen and Frank Lloyd Wright among them. In 1972, he completed work on his own home, near Cranbrook, which had by now transformed from wilderness into suburban sprawl. As an architect, Yamasaki took the Modernist project more literally than any of his contemporaries — he truly believed he would improve people’s lives through his work, and that his buildings were monuments to “man’s belief in humanity.”

And yet, Yamasaki has the odd distinction of being best known for two projects that were destroyed in a highly public fashion, leaving mass devastation in their wake: Along with the World Trade Center, there was also the federally financed Pruitt-Igoe housing project in St. Louis, which was completed in 1956. Originally conceived as a lower-income, racially segregated (blacks in the Pruitt section, whites in Igoe) development with a mixture of high- and low-rise buildings and green spaces in between, the Public Housing Administration’s push for higher densities necessitated drastic revisions, resulting in a 33-building vertical city that bore little resemblance to Yamasaki’s initial vision. As its occupancy declined throughout the ’60s, Pruitt-Igoe deteriorated into a breeding ground for crime and vandalism. State and federal authorities, agreeing that the complex was beyond help, began demolishing the buildings in 1972. Yamasaki became the chief symbol of the failure of Modernist architecture’s utopian optimism and of urban renewal’s contribution to the American city’s downfall.

IV. The City

THE COUNTRY HAS imposed a narrative myth upon Detroit: that it was one of the iconic modern cities until the riot of 1967, one of the worst race riots in the country’s history, which caused hundreds of millions of dollars in property damage and resulted in the abandonment of the city by the middle class. The reality is that Detroit’s modernization is what most contributed to its collapse. In 1963, as David Maraniss recalls in his 2015 history of Detroit’s heyday, “Once in a Great City,” Wayne State University’s Institute for Regional and Urban Studies issued a report predicting that Detroit’s population — about 1.7 million as of the 1960 census — would decline by roughly a quarter by 1970 as a result of people increasingly leaving the city for the suburbs. With more businesses opening in the suburbs to support a growing middle class, there was less and less incentive for people to live and, more important, work in Detroit. The previous decade of construction, which had brought such remarkable architecture to downtown Detroit, had produced little in the way of actual housing, and had in fact uprooted many of the city’s predominantly lower-class neighborhoods. As Maraniss writes, “Detroit was being threatened by its own design of concrete and metal and fuel and movement.”

This was the case in many American cities that had prospered during the manufacturing boom of World War II, only to find such growth unsustainable. But none suffered quite as much as Detroit: With its empty Art Deco skyscrapers and entire neighborhoods effectively erased from the map through abandonment and arson, the city inevitably became a symbol of postwar America’s rise and fall. After Detroit declared bankruptcy in 2013, the largest municipality to ever do so, downtown began to experience a development boom again thanks to the billionaire Dan Gilbert, who since 2010 has invested $3.5 billion in real estate downtown (with another $2.1 billion underway) and moved his mortgage company, Quicken Loans, and other businesses into the buildings.

In January, I walked around the city with Brian Conway, Michigan’s state historic preservation officer and the co-author of a two-volume series of books called “Michigan Modern.” We visited the Wayne State campus and Yamasaki’s McGregor Memorial Conference Center, a miraculous white box with white marble floors and white marble columns leading up to a series of second-story pointed hexagonal column capitals. Triangular skylight panels are arranged in a grid on the ceiling. It was raining heavily, and the space was cold and drafty. We also walked through Albert Kahn’s staggeringly beautiful Fisher Building, completed in 1928, a year before the American economy collapsed, and which a placard in the lobby describes as the city’s “largest art object.” The interior is covered in gold detailing, with chandeliers hanging like white pine cones from the ceiling. The ceiling itself displays an enormous mural of nude women with musical instruments, including a harp, surrounded by eagles and laurels. The elevators have bronze doors, carved with images of deities, one of them holding a car in one hand and a plane in the other. The building, after years of neglect, sold in 2015 (together with the neighboring 11-story Albert Kahn Building) for $12.2 million to a pair of developers (they are among the few landmarked skyscrapers Gilbert has not purchased) and is starting to fill up with businesses, which serve as a reminder of just how much distance there is between Kahn and our current moment: Muting the drama of the building slightly were several signs in the lobby directing visitors toward a Subway sandwich shop inside Cadillac Place, the former General Motors headquarters, also designed by Kahn, which is connected to the Fisher Building through a walkway.

Inside Yamasaki’s Michigan Consolidated Gas Company headquarters (now One Woodward Avenue) — the architect’s first skyscraper, also owned by Gilbert, and a precursor of the World Trade Center — employees milled about on their lunch breaks. Just outside the door, there were classic markers of early-stage gentrification speckled throughout downtown: a Shake Shack, a Lululemon store.

This was, on one level, heartening: 10 years ago, these buildings sat largely empty. The return of businesses to downtown has been celebrated by the press: Publications from National Geographic to The New York Times have written about a Detroit revival. But what would it mean for the rest of a city that was, fundamentally, still struggling, as it had for decades, with wide swaths of its poorer residents still virtually cut off from these signs of development? According to a recent report in the Detroit Free Press, the city has the worst squatter problem in the nation, with thousands of homes owned by the Detroit Land Bank Authority serving as makeshift shelters. In a city that is now 80 percent black, “revival” seemed to mean “once again agreeable to the white middle class.” (Last year, Gilbert apologized for an unfortunate ad campaign by his real estate firm, Bedrock, which featured an image of a crowd of enthusiastic white people and the tag line “See Detroit Like We Do.”)

And so here we are again, back at the notion of endless progress, no matter the cost. But progress for whom? It is not only a quintessentially American idea but a Modernist one: Knock down the low-income neighborhood to build the factory or the condo tower or the sports stadium, and let history record it as human achievement. This was the case a century ago, and the whole country saw what happened the first time around. Michigan’s Modernist heritage is more than just history now up for grabs; it is also a cautionary tale.

The day before I left Michigan, I drove to the suburb of Southfield to see the former Reynolds Metals Regional Sales Office, designed by Yamasaki. Completed in 1959, it is an elaborate monument to aluminum in a city whose fortunes once depended on the material. The building sits directly off the freeway in a drab and mostly deserted office park. The late afternoon sun bounced off Yamasaki’s grille — a woven pattern of gold-anodized aluminum rings. In 1959, the building would have been surrounded by a pool that reflected the glassed-in lobby, with its white concrete floors and marble-and-aluminum reception desk. But Reynolds had long since departed. Most recently, the building was home to an LA Fitness, but it has sat vacant for several years. I got out of my car and walked up the steps to the front entrance. Someone had wrapped the railing with streams of Christmas tinsel. The front door was boarded up with rotting plywood. The decaying art piece off the freeway was for sale for $900,000. I got back in my car and left.

Recent Articles

From Denver to Hollywood to Detroit

This is the real life story of Don McElfish, a retired GM Designer.

Griffith Observatory

There’s no better view of Los Angeles (and the infamous Hollywood sign) than from the Griffith Observatory.

Making Time For The Process

Sometimes everyday life can get in the way of the things we love to do, so how can we make time? Brooklyn shows us how.

Detroit 1978

For a class assignment, a 17 year-old photography student took a Rollie 35mm camera and some slide film and captured these shots of Detroit in April, 1978.

[instagram-feed]